Annemarie convalescing after an ear operation

Annemarie convalescing after an ear operation

This is an extended obituary of my mother, Annemarie Maggs. A brief version is on The Guardian website at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/06/annemarie-maggs-obituary and was published in the printed newspaper on 1 August 2018.

Annemarie Maggs – the original Mirli

When my mother retired from Brunel University after 26 years, Professor John Burnett said of her:

There must be few people of whom it can honestly be said that they are irreplaceable … She cheerfully ministered to the wants of half a dozen staff and a hundred undergraduates. She has been far more than a secretary – counsellor, confidante, cook, nurse, surrogate senior tutor if not Head of Department … She has been the fount of knowledge, the social pivot of the department: “Ask Annemarie” has never failed to produce a helpful answer, a cup of coffee, an aspirin, sympathy or just a chat.

He might have added that her duties did not prevent her from looking after lecturer Lisanne Radice’s dog Mutton, whom Annemarie called ‘the Mutt Mutt’, curled up at her feet when Lisanne had teaching duty.

Annemarie Maggs was born Annemarie Zelníček in Vienna in 1924. Her mother, Marie Antonie Zelníček, had come to Vienna from Třebíč in Moravia, a province of Czechoslovakia, now the Czech Republic. Annemarie’s father, according to Marie, was Ludvik Szuchanyi; they were not married. It is possible that they met while both were music students studying at the Conservatoire in Prague.

Annemarie was fostered and then adopted by a Catholic Viennese couple Dora Rosa (née Radziwiller) and Wilhelm Hubert Riedel. Willi Riedel was the manager of a high-class outfitters—the well-known Viennese firm of Riedel & Beutel—with shops for men’s and women’s clothes on either corner of a block in the Stefansplatz in the centre of Vienna. The family apartment was above one of the shops in No 3 Jasomirgott Strasse—the street named after Heinrich II sometime Duke of Austria in the 11th century, from his frequent use of the expression “Ja so mir Gott helfe” (So help me God).

Annemarie Maggs – the original Mirli

When my mother retired from Brunel University after 26 years, Professor John Burnett said of her:

There must be few people of whom it can honestly be said that they are irreplaceable … She cheerfully ministered to the wants of half a dozen staff and a hundred undergraduates. She has been far more than a secretary – counsellor, confidante, cook, nurse, surrogate senior tutor if not Head of Department … She has been the fount of knowledge, the social pivot of the department: “Ask Annemarie” has never failed to produce a helpful answer, a cup of coffee, an aspirin, sympathy or just a chat.

He might have added that her duties did not prevent her from looking after lecturer Lisanne Radice’s dog Mutton, whom Annemarie called ‘the Mutt Mutt’, curled up at her feet when Lisanne had teaching duty.

Annemarie Maggs was born Annemarie Zelníček in Vienna in 1924. Her mother, Marie Antonie Zelníček, had come to Vienna from Třebíč in Moravia, a province of Czechoslovakia, now the Czech Republic. Annemarie’s father, according to Marie, was Ludvik Szuchanyi; they were not married. It is possible that they met while both were music students studying at the Conservatoire in Prague.

Annemarie was fostered and then adopted by a Catholic Viennese couple Dora Rosa (née Radziwiller) and Wilhelm Hubert Riedel. Willi Riedel was the manager of a high-class outfitters—the well-known Viennese firm of Riedel & Beutel—with shops for men’s and women’s clothes on either corner of a block in the Stefansplatz in the centre of Vienna. The family apartment was above one of the shops in No 3 Jasomirgott Strasse—the street named after Heinrich II sometime Duke of Austria in the 11th century, from his frequent use of the expression “Ja so mir Gott helfe” (So help me God).

Annemarie with her father in the Vienna Woods

Annemarie with her father in the Vienna Woods

Summer holidays were spent in a wooden cottage on the shores of the Wörthersee, a lake in the southern province of Carinthia where there was swimming, fishing, boating and walks through the woods picking mushrooms and wild raspberries. In the local dialect the name ‘Annemarie’ became ‘Annamirl’; the family shortened this to ‘Mirl’ and then ‘Mirli’, the name by which my mother was known in her youth (and which she heartily detested …)

In 1933 Hitler had come to power in Germany, and the following year, Dolfuss, the Chancellor of Austria, was assassinated by Austrian Nazis following a brief and limited civil war—my mother remembered the consternation among the nuns at her summer camp. In March 1938, Germany and Austria formally joined together—The Anschluss--and Hitler, Austrian by birth, marched in triumph into Vienna. At Annemarie’s school, the Oberlyzeum Luithlen, the pupils were immediately separated into Aryans and non-Aryans, although she said it was a matter of honour to preserve friendships across the racial divide. She was, however, obliged to join the junior girls’ version of the Hitler Youth, the Bund Deutscher Mädel.

But there was a far more ominous development than Annemarie having to march under a Swastika, because her adoptive mother Dora—she preferred her second name Rosa which she altered to 'Rosl'—was a secular Jew. She had converted to Catholicism when she married Willi, but in Hitler’s Reich, everyone was required to provide proof of their non-Jewish ancestry back three generations. It is because of this requirement that much is known of Annemarie’s background, including the identity of her putative father, although there is a glaring inconsistency in his records which the so-called Master Race apparently failed to spot. Racially though, Rosl was on the ‘wrong’ side. The increasingly brutal treatment of Jews in Germany and Austria was clear to everyone. Sigmund Freud had left Vienna in April 1938 for refuge in London following an invasion of his apartment by Nazi bully-boys—Jews had no protection from Common Law in the Reich—and Rosl was obliged to leave the country of her birth for her own protection. She took lessons in English cooking, and left Austria in the summer of 1938, finding employment as a cook in Britain.

In 1933 Hitler had come to power in Germany, and the following year, Dolfuss, the Chancellor of Austria, was assassinated by Austrian Nazis following a brief and limited civil war—my mother remembered the consternation among the nuns at her summer camp. In March 1938, Germany and Austria formally joined together—The Anschluss--and Hitler, Austrian by birth, marched in triumph into Vienna. At Annemarie’s school, the Oberlyzeum Luithlen, the pupils were immediately separated into Aryans and non-Aryans, although she said it was a matter of honour to preserve friendships across the racial divide. She was, however, obliged to join the junior girls’ version of the Hitler Youth, the Bund Deutscher Mädel.

But there was a far more ominous development than Annemarie having to march under a Swastika, because her adoptive mother Dora—she preferred her second name Rosa which she altered to 'Rosl'—was a secular Jew. She had converted to Catholicism when she married Willi, but in Hitler’s Reich, everyone was required to provide proof of their non-Jewish ancestry back three generations. It is because of this requirement that much is known of Annemarie’s background, including the identity of her putative father, although there is a glaring inconsistency in his records which the so-called Master Race apparently failed to spot. Racially though, Rosl was on the ‘wrong’ side. The increasingly brutal treatment of Jews in Germany and Austria was clear to everyone. Sigmund Freud had left Vienna in April 1938 for refuge in London following an invasion of his apartment by Nazi bully-boys—Jews had no protection from Common Law in the Reich—and Rosl was obliged to leave the country of her birth for her own protection. She took lessons in English cooking, and left Austria in the summer of 1938, finding employment as a cook in Britain.

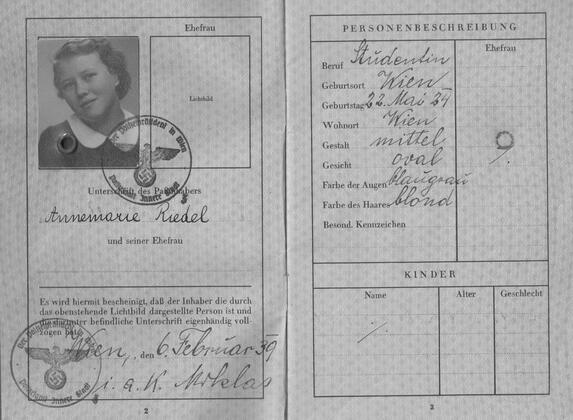

My mother's passport

My mother's passport

My mother was fourteen years old and young for her age, and Willi could not cope with her and the apartment and work. It was decided that she should join her mother in England. He deemed her too scatterbrained to find her way across Europe on the trains, so in April 1939 she boarded a KLM flight from Vienna to London via Rotterdam; she was wearing her Auntie Zenya’s fur coat and jewellery. Aunt Zenya was married to Rosl’s brother, and was also fleeing persecution. Annemarie arrived at Croydon Aerodrome where she was granted a six month visa to stay in Britain (which expired in October 1939…) She was not yet fifteen, and spoke only the English she had learned at school.

It was impossible for her to stay long-term with her mother who was a live-in cook, so the Sisters of the Sacred Heart in Hammersmith took her in as a refugee. When the school relocated to Cornwall because of the bombing, she went to stay with a Catholic family, the Pybuses, in Darlington. In 1940 when she turned 16, her status was reviewed by a committee in the Moot Hall, Newcastle-on-Tyne. She was confirmed as a category ‘B’ alien (who did not need to be interned) provided that her host, Cyril Pybus, agreed to lock up her bicycle and camera for the duration of the war, and she reported to the local police station for any nights spent away from home.

It was impossible for her to stay long-term with her mother who was a live-in cook, so the Sisters of the Sacred Heart in Hammersmith took her in as a refugee. When the school relocated to Cornwall because of the bombing, she went to stay with a Catholic family, the Pybuses, in Darlington. In 1940 when she turned 16, her status was reviewed by a committee in the Moot Hall, Newcastle-on-Tyne. She was confirmed as a category ‘B’ alien (who did not need to be interned) provided that her host, Cyril Pybus, agreed to lock up her bicycle and camera for the duration of the war, and she reported to the local police station for any nights spent away from home.

With Molly in Wales, circa 1942

With Molly in Wales, circa 1942

In 1941 she came back south, and after a period spent as an au pair, she was employed by Mars in Slough packing sweets and chocolate, and was able to enjoy the spoiled product (her mother could not understand why she kept putting on weight on war rations.) Annemarie’s workmates encouraged her to join them meeting boys and dancing at the Hammersmith Palais, and although she went once she did not enjoy it. Instead she joined the Linguists’ Club in The Kingsway; it was a place for learning languages and generally socialising. The very first person to talk to her there was my father, Norman Maggs, who had come to brush up on his German. In 1944, they had a narrow escape in Rosl’s flat in Barons Court. A stick of bombs killed some people further down the road, and fortunately only brought the ceiling down on my mother and father (who were, she said, ‘canoodling’); she suffered a cut leg. She was given lodging in my father’s parents’ house in Ealing, and in April 1944 they were married in Hanwell, and Annemarie became a British Citizen.

With me circa 1946

With me circa 1946

After a brief spell in Ealing, they moved to the country to avoid the bombing, living first in an ex-army tent in Bisham Woods, and moving into a caravan when Annemarie found herself to be pregnant. During my father’s funeral, an old friend of the family, Prudence, joined us in the car. Referring to my parents’ tent, I said, “So Prudence, I was started off in an ex-army tent …” “Yes”, added my mother in a rather loud voice, “Or in one of the fields round about…”

My mother and father

My mother and father

After the war Father and Mother moved back to Ealing. My mother took a course in shorthand and typing, and became secretary to the export sales manager at Sperry Gyroscope on the Great West Road in Brentford. Her knowledge of French and German was invaluable in that job. After Sperry relocated to Bracknell, she went for an interview at the Brunel College for Advanced Technology in Acton. In spite of getting her skirt caught in a large cut-glass ashtray on a low table, which she managed to dash into a thousand pieces on the floor, she got the job. When the college relocated to Uxbridge and became Brunel University, she went with it, travelling there by train and keeping bicycles at Ealing Common and Uxbridge Stations.

Garden party at the Palace

Garden party at the Palace

In 2004 on the occasion of their sixtieth wedding anniversary, my mother and father received congratulations from the Queen and the Pope. Norman and Annemarie lived in the same rambling house in Ealing from 1945 until 2008 when my father died. Through all of that time Annemarie supported Norman through the many trials and tribulations of his own life, never giving him less than 100% loyalty and support. After his death, she moved into sheltered accommodation at Albion Court in Chelmsford, where she was able to enjoy the benefits of central heating and hot running water for the first time in her life. She also greatly enjoyed the social life there.

In later life

In later life

Mother’s mobility gradually deteriorated as did her hearing; for a while she had a mobility scooter and would enjoy going to the park and feeding the ducks. In March 2018 she was admitted to Broomfield Hospital, after which it became clear that she was unable to live on her own any more. She spent the last six weeks of her life in the Okeley Care Home in Chelmsford, where she died peacefully in her sleep on 4 June 2018.

Everyone I have spoken to who knew her, all the cards, letters, and emails I have received have said the same thing: what a lovely, kind, sweet, and friendly person she was; she loved everyone and everything.

Everyone I have spoken to who knew her, all the cards, letters, and emails I have received have said the same thing: what a lovely, kind, sweet, and friendly person she was; she loved everyone and everything.

She took pleasure in the simplest of things: a single flower in a garden, a beautiful sunset, or a crescent moon. But she was also very widely read, and used regularly to do crosswords in English, French and German. For several years at Brunel University she was personal secretary to Lord Vaizey, the notable economist and educationalist. It was said of him that he refused any decision of which she did not approve. John Vaizey died in 1984, but I have had condolences from his whole family, two of whom commented that in different circumstances my mother could have been an academic herself.

Peter Maggs, July 2018

Peter Maggs, July 2018