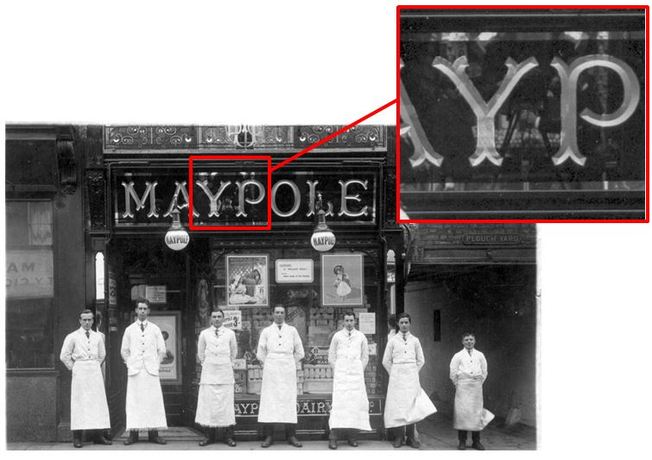

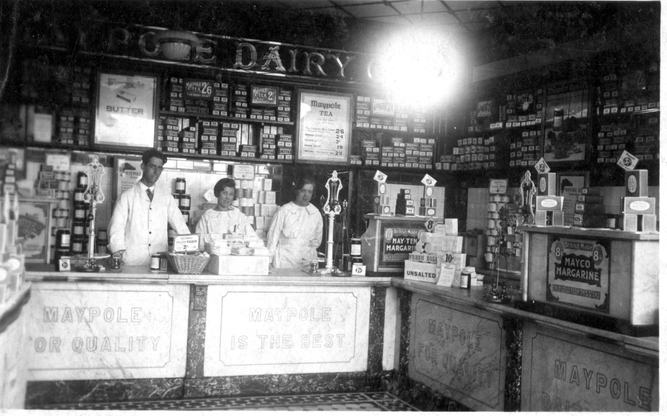

A family member asked me about an old photograph, and this started a chain of memories which deserve recording. My grandfather, Ernie Maggs, was employed by the Maypole Dairy from 1907 until 1934. He had a four year ‘break’ during World War I, when he served as a marine on HMS Canada, a Dreadnaught battleship that saw action in the Battle of Jutland. Ernie wrote a short account of his part in that conflict which is, I believe, in the archives of the Imperial War Museum. The first photograph shows Ernie, second from the left with the tasselled apron – as manager – presiding over the opening of a new Maypole Dairy in Brentford High Street. On his left is his brother-in-law, Cyril; he was deputy manager and had shorter tassels… What is fascinating about the picture, is that the photographer, complete with large camera mounted on a tripod, can be seen reflected in the glass ‘Maypole’ banner over the top of the shop. Furthermore, the event can be fixed unequivocally in time and space; it was the day my father was born, in February 1921, and the shop was next to the entrance to Plough Yard in Brentford. The origins of the Maypole Dairy go back to 1839 when James Watson, MP for Shrewsbury, established a butter and provisioning business in Birmingham. This was acquired by George Jackson in 1859, although the Watson family carried on a similar business ‘without opposition’ to George Jackson. The Watson business traded as the ‘Maypole Dairy’, and in 1898 the two decided to merge under the name The Maypole Dairy, with 185 shops and 17 ‘creameries or butter factories’. By the time that the Brentford High Street branch opened there were nearly 900 branches around the country. The Maypole was an archetypal “Pile ‘em High and Sell ‘em Cheap” chain. They sold tea, margarine (invented in France in 1869) and butter and very little else. 15 years later in Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell reported that margarine and tea were two of the main staples of poor working-class families in the north of England. This was the Maypole’s business model; provide a large part of the population with several of their basic essentials at rock-bottom prices. In 1921, turnover was £36,500,000, generating a net profit of 3% or £1.1M. That translates to a profit of around £1,200 per retail outlet so there was money to be made. The second photograph shows Ernie inside a shop – it may or may not have been the one in Brentford, although he looks a similar age in both. It is fairly clear that apart from some jam and a few eggs, tea, margarine and butter formed the bulk of goods for sale. Most of the Maypole butter seems to have been imported from Denmark, and margarine was made at the Maypole’s own factory at Southall, Middlesex. Copra (coconut) and ground nuts were imported from the Far East and Africa to provide the oil to make the margarine; animal fat may also have been used. But nothing lasts. In 1934, not long before Orwell started his pilgrimage to the north to do the research for his book, the Maypole’s profits had fallen to £312,162, 28% of what they had been in 1921. There were many contributing factors but it was the middle of the depression, and their staples, margarine and butter, were getting competition from lard and butter from the antipodes. In respect of the latter, the chairman commented: “…unrestricted production in New Zealand and Australia have resulted in huge quantities of butter being shipped to this country at prices which, to put it mildly, cannot possibly be remunerative to the producer…” After 27 years service, when Ernie sometimes spent until one o’clock in the morning making window displays for the shop and gave over his Sundays to doing the accounts, he was summarily dismissed with one week’s wages. He was not alone and joined more than three million others out of work in the UK.

2 Comments

A correspondent takes me to task for my previous post ‘Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll’, where I explained my limited access to alcohol and drugs in the 1960s, but not to sex. Ah well, in my adolescence I did suffer from severe acne, and such girl-talk as I have been privy to leads me to believe that spots were quite an effective anti-aphrodisiac.

I tried all sorts of remedies at the time including sulphur tablets. These had the unfortunate anti-social consequence of producing rather unpleasant ‘wind’. I recall on one occasion I was with the other members of the band in our Transit Van driving through Acton High-Street. I was unable to control a sudden pressure build-up, and the effect in that confined space was staggeringly awful. The van came to a screeching halt diagonally across the road, the doors were flung open, and my comrades exited the vehicle in all directions. The most upsetting thing was that the tablets had absolutely no affect at all on the incidence of spots... It is a cliché in TV detective dramas like Morse, Lewis and Poirot, how a tiny clue can open up a completely unexpected and fruitful line of enquiry, but it does happen in real life forensic genealogy.

As part of my investigation into the Red Barn murder, I wanted to find out what happened to William Corder’s posthumous son, born three months after Corder was hanged for the murder of Maria Martin. The authors of two previous books on the affair had claimed that he died in infancy, either within hours of the birth, or about nine months later. Following some correspondence with another writer on the Red Barn, I was made aware of a piece in a local newspaper in Cornwall in the summer of 1893. A brief note stated: About a month ago the son of Corder, the murderer of Maria Martin in ‘the red barn’, died in a lunatic asylum. William Corder’s son, John, was known to have been born with a withered arm and was said to be of ‘weak intellect’. Other newspapers of the period were searched, but this was the only reference that could be found. A search of the death indexes of the period showed that a John Corder of the right age had died in Essex in late 1892. Furthermore, the Essex lunatic asylum was located within the area where the death was registered. A copy of the death certificate showed that the John Corder in question had been a bookseller in Colchester. This revelation was greeted with disappointment; John Corder with a ‘weak intellect’ could not possibly have been involved in selling books. However, a routine check on book-seller John Corder in the census returns revealed him to have been born in Polstead, where the Red Barn murder took place… He had been a well-known character in Colchester and there was even an obituary, but in all the local newspaper references to him, the Red Barn affair was not mentioned once. Then the record of a court case was found where John Corder had encouraged three farm-workers from Polstead to remove some crops from a field there because Corder believed that the land rightfully belonged to him. One of the witnesses said in court that he had seen Corder’s father hanged… Here was proof positive; John Corder, book-seller and newsagent of Victorian Colchester, was the son of William Corder, the Red Barn murderer. |

AuthorWelcome to the Mirli Books blog written by Peter Maggs Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed