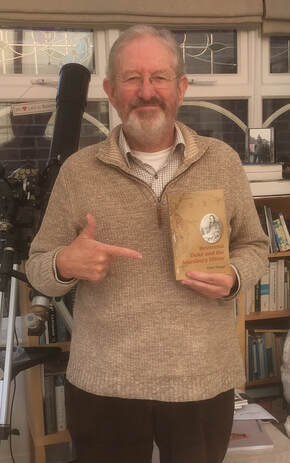

For five years I have been toiling on this new book, Reverend Duke and the Amesbury Oliver. The last six months have been spent just editing the final version for print. It has been the most difficult thing I have done, but now it is published. I recount the quite extraordinary behaviour of the Reverend Edward Duke, 1779-1852, antiquary, magistrate, and guardian of the Amesbury Union Workhouse. The introduction to the book can be read here. The new book is available directly from me via this website, or from all reputable online booksellers, including the one named after a South American river, and high-street shops—if any of them are still trading. A short account extracted from the book will be published in Genealogists’ Magazine in due course. A summary of Mr Duke’s bizarre theory concerning the origin of Stonehenge, Avebury and Silbury Hill can be found here. Keen observers may note that my appearance has undergone a subtle change over the last few months. I blame general indolence and shortages of razor blades due to panic-buying.

0 Comments

I suspect that the phrase ‘UK Energy Policy’ might well be an oxymoron. With the exception of subsidies given to wind farms, there is little to suggest any sort of comprehensive plan.

Here are some statistics that I find uncomfortable. Yesterday at various times, natural gas provided more than 50% of UK electricity power generation. Since the demise of coal, combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) generators provide the lion’s share of UK power needs. They are efficient—up to 60% is claimed; the gas turbine exhaust heat is used to generate steam, which drives steam turbine generators—and notwithstanding the CO2 emissions, CCGT is relatively clean. They can also be started up in half an hour or so in order to meet rapid variations in demand. So far, so good. But natural gas is a fossil fuel, and there are proven world-wide reserves of gas that will last for only slightly more than 50 years at current consumption rates. Undoubtedly more will be discovered, but the bad news is that more than 40% of known reserves lie in Russia and Iran, with Russia holding more than 24%. Even the most liberal of observers could hardly claim that either country is a friend of the UK, so there must be a major question of security of supply; more than 50% of our gas is imported and our own natural reserves are now substantially depleted. As I remember well during the oil crisis of 1973, the OPEC countries increased the price of oil by 400% and the price of petrol at the pumps more than doubled within a few months. It seems to me that natural gas may well be a strategic weapon of the future. Economies are based on the availability of electricity, and without gas to heat our homes and offices … True, there is a plan to phase out domestic heating with natural gas, and 30-40% of consumption is used for that purpose. I do wonder though at the reality and cost of replacing 22 million gas boilers over the next ten years. I suspect that, with a few exceptions, only new homes will be fitted with alternatives. Nuclear power will not come to the rescue either. Hinkley Point C is enormously expensive although it is planned to provide 7 - 10% of our ‘current’ power needs, and there has been a shambles over financing and planning. Frustrations with financing have caused Hitachi to pull out of two new UK nuclear projects in the last few months. It is tragic that the UK, which produced the world’s very first commercial nuclear-powered electricity generation, is now not only dependent on imported technology, but seems unwilling to pay for it. And there is always the problem of security against hostile action. In these days of state-sponsored terrorism, anything is possible. A single, well-placed, air to ground missile could easily take a nuclear power plant off line for months, years, or for ever. Not even a missile would be needed. Remembering Chernobyl, what manager would risk operating a nuclear plant that had been damaged, no matter how slightly. There is one more problem for future electricity generation that I suspect might be the elephant in the room. Within ten years no new petrol or diesel cars will be sold in the UK. All those new electric cars and other vehicles will need electricity. Apparently there are now in excess of 40 million cars, vans, busses, and lorries on UK roads. That is potentially a lot of extra electrical power needed in coming years. The answer seems so burningly-obvious to me, that I wonder why we are not doing it already. One of the real successes of green energy policy, has been the proliferation of wind turbines. People moan that they are unsightly, although most are situated offshore. Others moan that the operators are sometimes paid not to generate electricity, but if that is the case, it is because they are flexible, and no-one yet has come up with an effective way of storing large amounts of electrical energy when generation exceeds demand. The main drawback of wind turbines is uncertainty in the wind. The website gridwatch.co.uk indicates how different technologies—nuclear, wind, solar, hydroelectric, CCGT etc.—contribute to UK power demand. Over the last few months, I have seen wind power provide from 40% of the country’s entire electricity needs, to just a few percent, entirely depending on the weather. The one resource, untapped, eminently renewable, entirely predictable, distributed all around the country, and needing technology that has been mature for decades, is tidal power. The tides rise and fall twice every day. There is a monthly variation according to the disposition of the sun and moon, but that amounts to only 30% or so, and can be predicted with a high degree of precision. Furthermore, the time of high tide varies around the country. The process is simplicity itself—and has been used for hundreds of years to power the milling of corn. Build a lagoon, and install turbine generators in the wall of the lagoon. As the tide rises, the water flows into the lagoon through the turbines and generates electricity. As it falls, the water flows out of the lagoon and generates electricity. In practice, sluices are closed at the beginning of the rise and fall to allow a head of water to build up; this reduces the availability of power generation to around 14 hours in every 24. But since there is always high or low water somewhere around the coast, careful positioning of generator sites could provide full, uninterrupted coverage. There could be a further benefit. Much of the east of England, particularly Essex and Suffolk, is sinking into the sea. Since I lived at Wivenhoe on the Colne estuary in Essex in the 1970s, the sea-level has risen there by 40 mm. The cost of coastal protection is high and some say ultimately a waste of effort, since eventually the sea will overtop any man-made defences. But a tidal lagoon doubling as coastal defence would change the economics completely. Might this be an answer to the east-coast problem? No-doubt there are some defects in these arguments, but I am certain that the basic principle is sound: renewable, relatively low tech, and distributed power generation, with added benefits, as part of future energy policy. Isn’t this exactly what the country wants right now? A massive infrastructure project providing employment for tens of thousands, and a real strategic asset for the whole country. In 2015, having completed the research, writing, and publication of my last book on the Red Barn murder, I decided to resurrect a narrative my father wrote in the 1960s but which was never published. His genealogical researches had uncovered a previously unknown judicial enquiry into the death of a crippled and consumptive orphan boy at the Amesbury workhouse. The master had been accused of flinging the boy against a flint wall where he cut his head. Five weeks later, the boy was dead. The enquiry had taken place in 1844, and Father decided to write it up as a historical novel.

Casting around for something to do, I read Father’s manuscript, and decided to have a look at the files on which he based his account. These now resided in the National Archives at Kew. The files contained the correspondence that had taken place between the Poor Law Commissioners, the guardians of the Amesbury Union, and the Reverend Edward Duke. Duke was a local landowner, antiquarian, JP, and ex officio guardian at the workhouse. It was Edward Duke who had made the original charges against the workhouse master in a letter to the Home Secretary. And for the previous nine years he had inundated the Poor Law Commissioners with letters complaining about the conduct of the Amesbury Union. When I started the process, I realized that I would have to read every piece of relevant correspondence in order that no clue as to the background of this extraordinary affair should be lost. Even now, I’m not sure that had I known the labour that would be involved, I would have started it. Edward Duke wrote to the commissioners around seventy times between 1837 and 1844; his letters were always of four pages or more, and his handwriting was very challenging to read. Other correspondence was of greater or lesser length. The original evidence from the enquiry was on 100 pages of foolscap in handwriting that was truly appalling. Of the latter, my mother had transcribed around 30% of the text; she was a shorthand typist, and well versed in reading difficult script. She was also able to decipher a number of shorthand symbols that were used, and thus she provided me with a sort of ‘Rosetta Stone’. This made the transcribing of the remaining 70% of the evidence much easier that it would otherwise have been. In all, around 270 individual pieces of relevant correspondence, each one containing an average of four pages or thereabouts, had to be read. Fortunately, the National Archives allows cameras to be used, and I was able to photograph the documents, and enlarge them on a computer screen to aid decipherment. The next job was to make transcripts of the important documents. This done, the writing could commence, and early in June of this year I finally submitted a manuscript for laying out. I have been updating, editing, checking, and fettling ever since. Finally yesterday, I gave the go-ahead to print the thing. The last six months have been a nightmare. I had a punctuation melt-down from which I have yet to fully recover, and despite numerous read-throughs by several other persons, typos kept appearing with monotonous regularity. I continued to find instances where I had made an error of interpretation. Almost the final straw, barely two weeks ago, was to discover by a chance remark from a correspondent that I had been calling the master of the workhouse ‘The Governor’, when that was his informal title bestowed upon him by the paupers. Anyway, it is done, and from January the book will be available from the usual online retailers and all good bookshops. Also, it can be obtained directly from me via this website. Residents of Chelmsford and the surrounding area can have the book delivered COD. I doubt that this new work will make the smallest ripple in the book world, but I have at least succeeded in bringing before the public what I think is an extraordinary story, one that my father discovered so many years ago. |

AuthorWelcome to the Mirli Books blog written by Peter Maggs Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed