|

The Law of Unexpected Consequences frequently works to frustrate human endeavour, but it might just have worked for the public good. Much has been made of the fact that the Labour Party polled fewer votes in last Thursday’s General Election than in 2019 when Corbyn was in charge. He was campaigning against Johnson who subsequently won an 80-seat majority. That result was skewed by several factors. Corbyn and Johnson were both divisive in their different ways, voters either loving them or hating them. Johnson’s showy cosmetic charm and bonhomie endeared him to many voters and revolted others. Likewise Corbyn’s agitprop socialism generated adoration and loathing. Crucially though, Farage’s B****t party refrained from standing in seats where Conservatives were likely to win. This time, notwithstanding Starmer’s total rebuild of the Labour Party, ‘Fag-Ash’ Farage took the gloves off and was undoubtedly responsible for the Tories’ rout. This was an election lost by the Conservative Party, and only won by Labour by default.

However what do we see? Outgoing Sunak and Hunt have dubbed Starmer a ‘decent and honourable man’ as if that were an unusual trait in a Prime Minister! The new health secretary is sitting down next week with the junior doctors to try and resolve their dispute—scandalous that the Tories cynically allowed it to drag on for so long. The disgraceful Rwanda scheme goes into the dustbin of history, and Starmer is doing the rounds of the Union to cement his inclusive attitude to the four nations. Make no mistake the new government have some very difficult challenges: the health service, community care, the cost of living crisis, housing, prisons, and of course immigration, all with very little financial room to manoeuvre. If they can make some progress that people can actually see over the next few years, then Fag-Ash’s declared aim for a take-over in the 2029 election will wither on the vine. He gambled in 2024 and achieved his immediate objective. But he also allowed decent people into government whose efforts, if they succeed, may well condemn him and his band of bigoted, xenophobic, nationalist cronies to join the Rwanda scheme where they all belong. As an addendum to these thoughts I listened to a very interesting discussion on the BBC this morning. It was to the effect that the Europe of now is very different from the Europe that this country voted to leave in 2016. There is a definite surge to the right in a number of countries—anti-EU, anti-immigration, equivocation on Ukraine etc. Interesting times. For the record, last week I formally applied for citizenship of Austria. I’ll do a modified ‘Vicar of Bray’ for as long as they’ll let me and keep a foot in both camps.

0 Comments

“...And the skies over England were dark with lame ducks—the streets were clogged with chickens coming home to roost...”

(An unfortunate juxtaposition with the title of the previous post which I have only just noticed... I'm sure my reader will be suitably amused.) What is going on in the Sunday Telegraph? Quoting Stalin? Initially I was perplexed. Having thought about it, the reason appears to be quite sinister.

The solution to today’s ‘Quote down’ word puzzle is an epigram attributed to Joseph Stalin. It goes: “Those who cast their votes decide nothing. Those who count the votes decide everything.” Reprising this hyper-cynical notion immediately before an election that is likely to see the paymasters of the Telegraph organization thrown out on their collective ears, suggests a rather Trumpian disregard for the democratic process. The so-called debate between Sunak and Starmer on the BBC last night was very unsatisfactory. I’m tempted to repeat the sentiments of one of the audience who asked a question something like ‘Are you two the best on offer?’ They frequently talked over each other, and on several occasions the two of them and Mishal Husain were speaking simultaneously. Sunak though was the worst by far; constantly interrupting and talking over the others. With the state of the polls he has nothing to lose. And in almost every sentence he told us that he was going to cut taxes; Labour was going to raise them.

I wondered why Starmer hardly challenged him on that point except when he repeated the £2,000 tax lie again. The truth is, and this has been pointed out elsewhere, that neither of them has any choice in the matter. The country’s finances are in a perilous state—the on-going cost of the financial crisis, Covid, Ukraine, poor productivity, and losses from our departure from Europe. Whichever party forms the government—and I would love to see a coalition to force the buggers to work together for the public good—they will have stark choices. The public services are on their knees and money can come from only three sources: further cuts in public services—unthinkable; more borrowing, or increased taxes. There is also the uncomfortable—and unavoidable need to increase defence spending. In my view neither leader was telling the truth about the finances because for either to admit it, would be to commit instant political suicide. The other issue was immigration. Once again, neither of them told the truth. Legal immigration, at an all time high, outweighs so-called illegal immigration—those who arrive on small boats—by more than ten to one. But there are still the 50,000 or so asylum-seekers who are here, not permitted to work, and being housed at government expense. From what I have read, I believe that the overwhelming majority, once processed, are granted asylum. Sunak wants to fly the lot to Rwanda, a policy that would have done credit to the Third Reich. Starmer pointed out the reality that a) the deterrence is clearly not working since they—the asylum-seekers—know that only a very small majority will be denied asylum and flown to Rwanda, and b) in any case the process would take three years and they’re still coming... For his part Sunak repeatedly asked Starmer what he would do about them and answer came there none. Neither of them risked declaring the truth that without immigration our public services, service industries, and farming would collapse for lack of manpower. It is difficult to see how the next government can possibly be worse that the current one, but I fear that things are not going to get better any time soon and will probably get worse. One of the very first Italian words I learned in Rome in the summer of 1965 was “Frocci”, an insulting term applied to me and my fellow band members on account of our long hair. We were told that it meant “Queers”. The word recently used by Il Papa, “Frociaggine”, Google Translate renders as “smoothness”, clearly a word related to “Frocci” betraying its etymology.

It really isn’t a great advertisement for Pope Francis to use such language, particularly since his native tongue is Spanish. Furthermore, to use the word when addressing a collection of Catholic bishops, and in camera, betrays an astonishing level of hypocrisy. I’m surprised and yet not surprised at this, since it just confirms my own views about The Church. Any attempt to portray recent popes as having dragged Catholicism out of the Dark Ages is shown to be entirely spurious. I wonder how many people hung up their rosary beads as a result. For the best part of sixty years I have been fascinated by philosophy. My bookshelves groan under the weight of publications on the subject, from Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, to Cathcart and Klein’s Plato and a Platypus go into a Bar. Of the former I got lost on page 6—and pages 1-5 were the preface... Plato and a Platypus is quite hilarious, and is an exposition of philosophy through mainly Jewish-American humour. I have read many other similar books, but to date the only knowledge on the subject that I have firmly committed to memory, is Monty Python’s Philosopher’s Song.

I’m now trying—for the umpteenth time—to read Bertrand Russell’s surprisingly accessible History of Western Philosophy. I have reached the point where he is expounding the theory that Plato might well have ‘invented’ Socrates. The argument is that what he (Plato) says about Socrates conflicts with Xenophon’s version of the man. Xenophon, like Plato a pupil of Socrates, was ‘not very liberally endowed with brains’ and ‘conventional in his outlook.’ Russell’s thesis is that the Platonic Socrates—the Socrates described by Plato—was a fascinating and most interesting character, substantially embellished, Russell suspects, by Plato’s considerably literary and intellectual talents and possibly even expressing Plato’s own ideas. It is fascinating stuff but by tomorrow I shall have forgotten it. I am reminded of an incident during my graduate student days. I was most fortunate to have Professor Alan Gibson, FRS, as my supervisor. He was an astonishing man; not only a gifted scientist and educator but also a very able administrator. I struggled during my research project which did not start well when I made it very clear to him that I did not understand Ohms Law... We were at an Opto-Electronic conference in Manchester. Alan was due to present a keynote paper first thing in the morning that followed an evening spent by me carousing in the bar. On going to bed I wondered why my travelling clockwork alarm clock was showing the completely incorrect time. I reset it, adjusting the alarm to wake me up in good time for Alan’s lecture. It did wake me up, but it was only that evening on coming back to the room that I realised that the reason the clock appeared to be wrong was that I had placed it upside down... There must be a wonderful metaphor there, but for the life of me I cannot find it. Anyway, I attended Alan’s talk and it was one of those rare Damascene events. As I listened to him explaining with complete clarity a most abstruse and subtle point, the scales were lifted from my eyes and for a few precious moments I was able to understand something that until then had completely eluded me. I never forgot the incident, that is to say the magical feeling of comprehension; the point itself was lost to me by lunchtime that day. I shall soldier on with Russell. At the very least having forgotten it all from the previous reading, every new idea comes as an exciting revelation. In our Time, the regular discussion programme chaired by Melvyn Bragg, is the very best of BBC Radio. Each week three working academics are assembled to discuss a topic chosen from an enormously diverse range of subjects in the arts and sciences. Some weeks are better than others. Sometimes an interesting subject is spoiled by poor communicators; likewise, an apparently dull topic can be made fascinating by gifted and informed academics. Occasionally, and last Thursday (29 February) was an occasionally, a set of great and knowledgeable communicators discuss a really fascinating subject and the programme positively catches fire.

The subject in question was Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. The academics: Fay Dowker from Imperial, Harry Cliff from Cambridge, and Frank Close from Oxford, were at the absolute top of their game. Apart from the thoroughly lucid way each one of them dealt with the subject, they were relaxed, there were a few jokes and some light-hearted banter, and some superb analogies: atomic and molecular spectra were likened to a bar code. Quite brilliant! The Uncertainty Principle states that if you know the position of a particle fairly well, it’s momentum is uncertain. Likewise if you know its position in time accurately, you don’t know its energy. The consequences of this for many aspects of science are huge. I think it was Harry Cliff who cracked the joke: Heisenberg gets stopped for speeding. “Do you know how fast you were going?” Says the officer. “No”, he says, “But I know exactly where I was...” I have listened to the programme twice now—including the extra minutes on iPlayer—and I can say with some confidence that for anyone who is interested in science, cosmology, or even philosophy and religion, this programme is a must. I think it is probably the best In our Time ever. As a ‘Sixties Science Fiction nerd I have been vegging out on classic Isaac Asimov on Audible. They have the original Foundation series, the I Robot stories—so much better than that cretinous Hollywood film abortion—and the Robots and Empire books. They're dated but by jingo Asimov could spin a great tale!

It’s all interspersed with Jeeves and Wooster as narrated by Stephen Fry. All highly amusing and escapist stuff, but these days can anyone suggest anything better? Answers on a postcard please ...

Many people driving under Ironbridge, where the Great Western Railway crosses Uxbridge Road in West London, will be unaware that it consists of three bridges side by side. And since two of them are composed of two spans of a different character, there are actually five bridges there. However Ironbridge is not to be confused with Brunel’s famous Three Bridges (which are actually only two), only a few hundred yards away where a road crosses a canal, which itself crosses over a railway line at the same point.

The illusion (that there is just one bridge there) at Ironbridge can be understood from the attached pictures, courtesy of Google Maps, which show views from either side of the ‘bridge’.

But, I hear you say, if there are five bridges there, where are the other two? To answer that, we must go back 189 years to 1835 when Brunel was planning his Great Western Railway. Immediately after the Wharncliffe Viaduct, that magnificent series of brick arches crossing the valley of the River Brent just after Hanwell Station, Brunel had to bridge what was then the Uxbridge Turnpike. And being Brunel and, in a perversity that he was to repeat more than twenty years later with his Three Bridges, he elected to design a structure to cross the turnpike at the exact point where it was crossed by Windmill Lane (and Windmill Lane is the road at the Three Bridges).

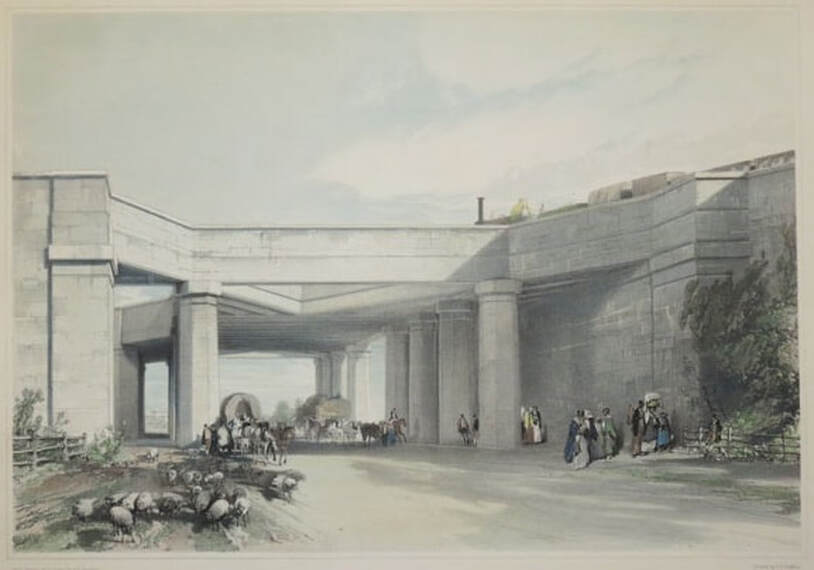

The difficulty of building a bridge across a crossroads was compounded by the fact that the railway crossing was highly skewed; the angle between the main (Uxbridge) road and the line of rails was only 23°—equivalent to a ‘skew angle’ of 67°—meaning that from simple geometry, the length of a single span would have to have been more than twice the combined width of the road and walkways on either side. The Act of Parliament authorising the building of the GWR required a forty foot width of road with two walkways each of ten feet either side. To cross a 60 foot gap at a skew angle of 67° requires a bridge span of more than 150 feet. Because of the highly skewed angle, an arch bridge either in brick, stone, or cast iron would have been impossible. A girder bridge was the only viable option, but in 1835 the only girders available were of cast iron, and they were limited in length to around forty feet. Ever resourceful, Brunel first convinced the Commissioners of Roads to reduce the road width to thirty feet, the walkways to five feet each, and also to allow him to ‘straighten’ the Uxbridge Turnpike so that the skew angle was reduced to 60°. In addition he was permitted to reduce the height of the road somewhat. He then devised an ingenious structure using a number of intermediate columns to support a grid of cast iron girders, none of which was more than 34 feet in length. Two lines of eight columns each were erected on either side of the Uxbridge Turnpike between it and the walkways, and girders were laid longitudinally along their tops, supporting transverse girders over the roads. The gaps were filled in with brick arches. But Isambard was not content just to produce an elegant solution to an awkward engineering problem, he wanted to do so with a flourish and make a statement. It may be that the prospect of his proposed flamboyant design helped to persuade the Road Commissioners to agree to his reduction in the road width and the other concessions, since the bridge would undoubtedly be a notable and interesting landmark on the road. He designed it such that the approaches, when viewed from either direction along the Uxbridge Road, appeared to be symmetric. On the right hand side was the end of the embankment with its brick abutment; on the left was a brick ‘folly’ closely mirroring the masonry on the opposite side. There were also some leading overhead girders between the two, quite superfluous to the bridge structure, which created a sort of ‘proscenium arch’ portico, framing the lines of pillars and girders in a most dramatic way. The effect is strikingly apparent in J C Bourne’s beautiful lithograph of the bridge dating from shortly after its completion in 1839. The skew bridge at Hanwell was quite unique, and demonstrated Brunel’s determination to find original solutions to difficult engineering problems. In the early summer of 1837, after Brunel's skew bridge at Hanwell was complete but before the railway proper was open, one of the main girders failed. The girder weighed 8.5 tons and was supporting a dead weight of 50 tons of bridge, plus the weight of any trains passing over. Fortunately the bridge did not collapse; the grid of girders was fixed together using mortise and tenon joints and these, together with some tie-bars, and the substantial timbers which supported the rails held the bridge deck together. The broken beam was quickly shored up with timber, and the bridge reopened. On 8 June, Brunel wrote to Grissell & Peto, the contractors who had built the bridge, telling them ‘No time must be lost ... to remedy this serious defect’. It was a very serious defect, and there were two possible causes: either the girder was faulty, or it had been incorrectly designed—and the designer was I K Brunel. Subsequent events showed that the casting certainly was faulty; whether the design was also marginal is a moot point.

The Commissioner of Roads, Sir James McAdam, with whom Brunel had probably negotiated the significant concessions on the bridge specifications, had become alarmed by the failure and retained a consultant to investigate. Sir Robert Smirke had extensive experience with cast iron beams, having introduced their use into domestic architecture. His younger brother, Sidney Smirke, took over from him when he retired, and designed the famous circular readers-room at the British Museum. Robert Smirke visited the Hanwell bridge in the company of McAdam, and on 20 November 1837 wrote to the commissioners saying that in his opinion the design of the bridge was perfectly good ‘if sufficient means have been taken to prove the soundness of all the castings’. He had spoken to ‘Mr Brunel’ who told him that before the timber framing supporting the ironwork was removed (having been in place for five months at this point), this would be done. The entire bridge, including the new girder, would be proved by Passing over it carriages loaded with a much greater weight than will ever be required at other times, and as the work is now completed, I do not know how any other or better proof can be obtained. Smirke’s words suggest that he was not entirely happy with the situation. Evidently Brunel managed to satisfy him that the bridge was safe, and the Great Western Railway opened for commercial traffic from Paddington to Maidenhead on Monday 4 June 1838. All was well for nine months, but in 1839, the West Kent Guardian reported that on the morning of 18 March just as a train was passing over the bridge ‘passengers were thrown into the utmost consternation by hearing a report resembling that of a heavy cannon...’ The main girder on the other side had broken in half. This time it was a passenger-carrying train that had been passing over the bridge. A tragedy was averted by the interconnected structure of the bridge and again it did not collapse, but McAdam must have been furious given the previous tests and assurances, and Brunel would have been very seriously concerned. Wasting no time, the company had a gang at the bridge that evening to shore up the broken girder. To compound Brunel’s misery, Daniel Wood, a gravel-digger who appears to have volunteered as a helper to the gang, was killed when a two hundredweight baulk of timber being lifted into place fell ten feet on top of him; the inquest into his death was widely reported in the newspapers. Two days after the incident Brunel wrote to Grissell and Peto: The fracture is ... in the corresponding girder and nearly at the same place as in the former case and apparently from exactly the same cause. I have had a piece drilled off and it consists of a mass of half sand half iron. That casting too had been faulty; eight-and-a-half tons of molten iron contains a considerable amount of heat, and part of the mould, which was made of sand, must have collapsed into the liquid iron under the thermal shock leaving no outward sign. There was a flurry of correspondence. A Mr Bramah, probably the subcontractor to Grissell and Peto who had cast the girder, had written to Brunel expressing doubts regarding its design. Brunel ‘returned’ the letter to Grissell and Peto writing: Had Mr Bramah or you expressed any doubt previous to the commencement of the work and had you declined being responsible it might be right for you to repeat the grounds of your fears—but the result of the accidents that have happened have proved that there is no cause for alarm. That the unsound girder should have stood what it has done is the strongest proof possible that a sound one of the same dimensions would safely stand anything that comes upon it. Here is Isambard keeping his head, making a very good point regarding the design, and clarifying contractual (and moral) responsibilities should it come to an argument as to ‘who pays’. He, of course, had far more to lose than the cost of replacing a girder. The bridge failure was public knowledge, and it was vitally important to establish that although the casting was faulty, the design was not. A new girder was duly cast and proved at a different foundry, and evidently transported to Hanwell with great despatch. Thus on 18 September Brunel wrote to Sir James McAdam: It was quite accidental that the [new] girder was proved and carried down to Hanwell without informing you. The obtaining the casting had occupied so much time that everybody was anxious to lose no more ... the casting has all the appearance of being an excellent one, it has been carefully proved, we have no means of proving it at Hanwell and if this be required it must be transported [back] to Limehouse. But I can furnish you with certificates of the proof to which it was subjected, signed by highly responsible parties, the contractors Grissell & Peto, the foundry, Messrs Seawards and my assistant and this I trust you will consider sufficient as proving the fact Reading between the lines, it is clear that Sir James had wanted an independent inspection of the proving process before the new girder was committed to the bridge. McAdam decided to get his consultant to press Brunel on the matter, and Smirke demanded further proof of the soundness of the bridge. On 4 November Brunel wrote to him: The new girder has been fitted into its place at the Metropolitan Road bridge at Hanwell and is now ready for fixing. In consequence of your letter of 4th Ult I have considered what method could be devised for increasing the security of the work and propose for that purpose to lessen the weight to which the girder is subjected very considerably and to prevent any vibration from the passing of the trains being communicated to the cast iron by the following arrangement. 1st To remove the brick parapet walls which now rest on the main girder and which together weigh about 30 tons and to substitute cast iron plates weighing only about 6.5 tons and of sufficient strength to carry themselves as well as hold up the girder in the event of its breaking. 2nd To remove the small brick arches now forming the floor of the bridge and which with the concrete constitutes a load of about 70 tons now resting on the two main girders and to substitute a timber flooring weighing only 16 tons and upon which the rail timbers would be laid so that any vibration upon the rails could not be transmitted to the girders. The total reduction in dead weight will then be 78 tons 10 cwt or 39 tons 5 cwt upon each of the main girders having consequently a very great deal of excess strength while at the same time from the introduction of the timber and the cast iron parapet the girders will be exposed to less injury and would be supported in case of failure of such could then be considered possible. I trust you will approve of these proposals and that you will have the goodness to communicate such approval to Sir James Mc Adam as early as possible. I am under promise to him not to proceed with the fixing of the girder. The brick arches and their cement infill contributed 70 tons of deadweight to the two main bridge girders. In his letter to the contractors Brunel said that the new girder (the second replacement) had been proved to ‘78 tons, 11 tons more than his maximum.’ Thus the maximum design load per girder was 67 tons. The function of the brick arches was to provide a flat and continuous bridge deck for the rails as well as a walkway for maintenance staff; was it really good design practice for this relatively minor feature of the bridge to consume almost half of its load-carrying capacity? Furthermore when pressed, Brunel cheerfully replaced it with wood saving a weight of 54 tons! Likewise, a straightforward alteration to the parapets saved more than 20 tons. In his letter to Smirke of 4 November, Brunel had said that the new girder ‘has been fitted into place ... and is ready for fixing’. Exactly what this meant was clarified by a letter to Sir James McAdam dated 21 November, and judging by Brunel’s words, Sir James was far from happy. Brunel began his letter: My Dear Sir James, I have received yours of the 18th. I am sorry it does not show that courtesy and confidence which you have uniformly displayed towards me in former correspondence and which I feel I deserve at your hands. I regret that before assuming that I was about to do something ‘in violation’ of any understanding or request, you had not applied to me to ascertain if such were the case as you would at once have been satisfied that it was not so. There is more to be done to the girder before fixing than can now be completed by Sir R Smirke’s return; it has to be raised to its [final position] and marked then lowered or removed to be chipped and filed before it is ready to be fixed and this alone I am about to proceed with. That no further delay that can possibly be avoided shall take place when it is definitely determined what is to be done with it up to the present time the girder remains in the lane close by. This is not quite what he had said to Smirke nearly three weeks earlier. Then he said that the girder had been ‘fitted into its place’; now he appeared to be saying that that still needed to be done. He went on: I should add that your surveyor has informed my assistant that they shall not move the girder from where it is, that he should prevent it by constables. That is going rather far and not only threatening that which he has no authority to enforce but adopting a course which if he had the authority is totally uncalled for. It seems that there had been an unpleasant confrontation at Hanwell, and it is not difficult to deduce what had happened. A few days after the failure of the first girder Smirke and McAdam had inspected the bridge, and either by then or shortly afterwards, the faulty girder had been replaced before either of them could witness the proving. Subsequently Smirke had had a meeting with Brunel and was presented with a fait accompli in that only by accepting Brunel’s proposed method—using heavily loaded waggons—could the girder, by default, be proven to be good. McAdam was obviously suspicious that Brunel once again was trying to out-manoeuvre him. Brunel continued: You have requested that the girder shall not be fixed until Sir Robert Smirke is satisfied of its soundness or shall have arranged with me on the subject. I have no intention of neglecting that request but waiting Sir R Smirke’s return I am going on with all the preparation required and I informed Mr Brouse [McAdam’s surveyor?] that such was my intention He finished by appearing to invite Sir James to withdraw his letter, otherwise Brunel would have to make a formal response ‘entered upon the official correspondence of the office’—was this letter then not a formal response? Evidently ruffled feathers on both sides were eventually smoothed over, the new girder was fitted, the brick arches removed, the other alterations made, and the bridge was opened for business. But the law of unexpected consequences reigned supreme; in substantially lightening the bridge, Brunel had opened it up to a new and fairly obvious danger that was eventually to spell disaster, and not just at Hanwell. |

AuthorWelcome to the Mirli Books blog written by Peter Maggs Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed