|

Yesterday, on my government-allowed walk around the local field boundaries, I elected to listen via my iPod to Act III of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung. The opera, Twilight of the gods, details the fall and destruction of the gods and their fortress Valhalla, built up and finally annihilated by Wotan’s hubris, arrogance, greed and selfishness. It seemed to me a perfect metaphor for what is happening to us all – particularly governments around the world – made all the more apposite by the latest comments from WHO, to the effect that a vaccine for Covid-19 might not be possible. And to rub salt into the wound, recovery from an infection could be no guarantee against re-infection.

No doubt this news was greeted by most people with considerable dismay; none more so than those in the ‘at risk’ category like me. But how bad is this really? Around a third of the population of Europe was thought to have died from the Black Death in the 14th century. Bubonic plague killed 100,000 in London alone in 1665/6. The Spanish Flu outbreak at the close of Word War I was responsible for between 20 and 50 million deaths. Until the 1940s when antibiotics were developed, the majority of people not massacred by human agency died from infectious diseases. Victorian literature is crammed with people expiring from consumption (tuberculosis), smallpox and ‘fever’ (probably typhus or typhoid). Regular outbreaks of cholera killed tens of thousands, including my gt-gt-gt grandmother in 1849. For none of these conditions was there any cure. Throughout the entirety of human history, humans have lived (and died) with infectious disease. Nevertheless, it is a wake-up call. Perhaps it’s a warning. If I believed in divine retribution, I would say it was a judgement on our own arrogance and contempt for the planet; our incessant plunder of the world’s resources and headlong craving for profit above everything. It will certainly stress-test the government of practically every country, particularly ours. See the Sunday Times story ‘38 Days when Britain sleepwalked into disaster’. This piece is from one of the Dirty Digger’s organs, and he is a newspaper proprietor not noted for his hostility towards Conservative governments. Charles Darwin identified the process of evolution by natural selection, but he had no idea of the mechanism that caused organisms to change and evolve. Subsequent research has proved beyond doubt that random mutations in the DNA sequence are responsible for alterations in living things, and there is absolutely nothing that can be done to stop it. The process is built into the very structure of life on earth. In fact without it, humans would never have evolved. There is, therefore, an ever-present risk of new infectious diseases emerging as existing viruses and bacteria continue to mutate. Already, bacteria are evolving immunity to existing antibiotics, a matter of considerable concern to the medical community. We must hope that a vaccine can be developed and drugs found to mitigate the disease symptoms of Covid-19. Alternatively, we may just have to balance our innate gregariousness and wish to socialise, with the ever-present risk of catching the disease. Without a vaccine, life will never be the same again, that is until the next mutation …

0 Comments

The trade show was at the Krasnaya Presnya exhibition centre in central Moscow. My stand was a co-operative affair used by several companies, owned and managed by a married couple based in Germany; he was German, she was Russian. Facilities at the centre were primitive, so the stand was self-contained with a working kitchen – staffed by the manger’s mother-in-law – and eating and rest areas. It was there that I first tasted blinis with sour cream for breakfast, which after the food in the hotel was completely wonderful. The kitchen was not able to operate all of the time as the mains power was subject to random interruption, sometimes for an hour or more. And the primitive facilities in the building extended to the lavatories, none of which had lavatory seats. I was told that as soon as they were installed in public buildings they were stolen, such things being in short supply to the general public.

On the third day of the show, I neglected to bring the key switch for my equipment's power supply, and the manager’s wife insisted that I take her German-registered Golf and drive back to the hotel to get it. As she handed me the keys, she mentioned that if it started to rain, the windscreen wipers could be found in the glove compartment. This was normal practice in Russia, she told me, windscreen wipers also being scarce and only too easy to remove. The show hours were long and time dragged, but there was time off at the weekend and entertainment to be had in the evenings if you knew where to look. Taking the metro into the centre I wondered around Red Square. I queued up at a dingy café for tea and cake, the tea being supplied from an urn with milk and sugar already added. I was told that the British Embassy was worth a visit, and on presenting myself there and providing a cheque for five pounds drawn on a British Bank (cash, credit cards and travellers cheques not accepted), I was able to take temporary membership of the British Embassy (Moscow) Club. That evening we watched a special screening of Robin and Marion provided by an old mechanical film projector. Getting to the embassy was hazardous. I had to negotiate a very wide road and there was no crossing point. I started across only to see one of those familiar (then) convoys of sleek Russian limousines racing down the middle of the road and heading in my direction. The lead car yelled abuse at me via the loudspeaker on the car roof as they sped past. It was a very disconcerting moment. One night our host loaded all of us into his VW minibus and we went to a club out of town. There was eating and drinking and a very good live band playing western rock ‘n’ roll. We were stopped on the way by the police on some pretext. Our host reached into the glove compartment for his credentials and produced a bottle of Scotch, which having been passed to the officers for inspection appeared to satisfy regulations, and we were allowed to continue. I had my own encounter with the police a few days later. I had heard that there was music in the basement of the Intourist Hotel close to the centre. Entry was strictly only with hard currency (dollars) and there was Cossack dancing and other live entertainment. It was after one in the morning when I left, and there being no taxis around and supposing that the busses had stopped running for the night, I decided to walk back to my hotel. It was a pleasant night and there were very few people about. A policeman spotted me and walked straight towards me. I started to panic, wondering what local bye-law I had broken, or whether foreigners were even allowed out on the streets at night. Universal sign language soon clarified the situation; he was asking me if I had a cigarette to give him … I was wrong about the busses too. Three passed me as I was walking back. Being in Moscow I had to visit the Bolshoi. The ubiquitous Intourist agent at the hotel was able to provide tickets. I was standing behind an American who also wished to go to the opera. He asked what was available, and on being told said in a loud voice “Cosy van Tuesday?” I told him that I thought the opera was probably ‘Cosi fan Tutte’, adding that it was by Mozart. I settled for a double bill of ballet and a short opera, obviously staged for visitors. The ballet I don’t recall; the opera was Bluebeard’s Castle by Bartok. I am not a fan of Bartok and the piece reconfirmed that opinion in spades. Truly, the only thing I remember about the evening apart from the splendour of the theatre, was that during a fairly quiet part during the Bartok, I heard a telephone ring quite loudly somewhere (this was well before the era of mobile ‘phones). Intourist also provided tickets for an evening at the Moscow Conservatory for some Tchaikovsky piano music. Much of Moscow was drab and dreary, but there was excitement in seeing Red Square, St Basil’s Cathedral, the Kremlin and Lenin’s tomb, which I saw from the outside only. And it was really stimulating to visit the Conservatory and the Bolshoi, notwithstanding the indifferent programme at the latter. There was real history here, I felt, and I would love to go back. In the late 1970s I spent two weeks representing my company at a trade show in Moscow. The cold war was in full swing and I was a little apprehensive of travelling into the ‘Lair of the Antichrist’. I flew out with Aeroflot, and despite some anxiety regarding the safety of Soviet era jetliners, the three hour plus journey on a Tupolev 154 ‘Tridentski’ (three rear-mounted engines) was uneventful. The only real memory I have of that flight was the cabin service; the female flight attendant had the appearance and behaviour suggestive of a previous occupation as a camp guard in one of the gulags.

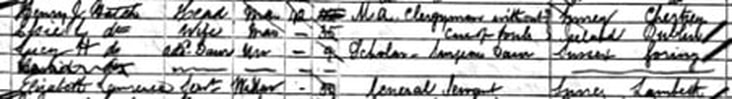

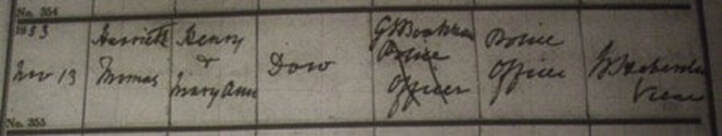

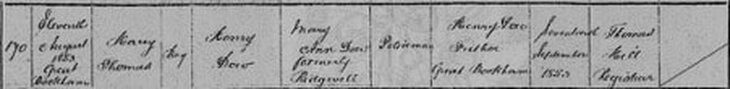

My arrival was not propitious. After an extremely long time getting through immigration, I learned that Intourist – the Soviet travel agency for foreigners – had allocated me a room in the Hotel Ukraina, a huge Stalin-Gothic pile around two miles from Red Square. Unfortunately though, owing to an extreme shortage of hotel rooms in Moscow – rumoured to be because of a local KGB jamboree – I was obliged to share the room with a complete stranger. Luckily my enforced companion was an amiable chap, the employee of a well-known British company. He was in Moscow for the same trade show that I was attending, and he invited me to dine with him and his two colleagues the following evening. We had a very good dinner but I was entirely unused to vodka, champagne and cigars – the last of which one of them insisted that I try – let alone the combined effects of all three. The consequence was inevitable and occurred in the room. My room-mate was very decent about it considering, and room service dealt with the problem without a murmur. The ‘floor-dragon’ – the formidable lady attendant standing guard on each hotel floor to safeguard the morals of the guests – seemed more amused than anything else; no doubt she had seen it all before. My companion told me that the Russian interpreter on his stand was a very attractive lady, and that he was having dinner with her on the following evening. He introduced me to her and she was indeed very pleasant; she taught me how to pronounce the name of the Soviet Union in Russian – Сою́з Сове́тских Социалисти́ческих Респу́блик – which went something like ‘Soyuz, Sovietski, Sozialisticheski, Respublic!’ The following evening came and went, and the morning after I found myself alone in the room… This was the obvious solution to the problem of sharing, and I’d like to think that it was the lady’s attractions and not my previous behaviour that precipitated this event. I had the room to myself for the rest of my time there. Two days before we were due to fly back to London, my new friend approached me at the exhibition and invited me to a party on the following evening at the lady’s apartment. He added, almost as an afterthought and rather sheepishly I thought, that it was to be an engagement party … He gave me the address written in Russian on a piece of paper, and on the appointed evening the taxi driver dropped me near an enormous apartment block somewhere in the suburbs. I had to use the written address at least twice more with various of the locals to locate the actual apartment. It was an excellent party. The received wisdom at that time was that the Russians were sinister Bolsheviks for whom anyone from the West was fair game to intimidate, rob or worse. In fact they were very friendly and most hospitable and not at all hostile or intimidating – with the exception of some of the officials. I have no idea how I got back to the hotel that night, but I did wake up there the next day after no more than three hours sleep. Not the best state in which to pack and then endure Russian customs control and a three hour flight – this time in an Ilyushin 62, a ‘VC10ski’ (four rear-mounted engines). I was very glad to get home, and ostentatiously declared my bottle of Russian champagne to the UK customs official; he dismissed me with a wave of his hand. Sometime later I did hear from one of his colleagues that my erstwhile room-mate had managed to get the lady out of the Soviet Union, and they were now married. But the last news he had heard, he said, was that she was unhappy living in England and was missing Russia… In my recent 15 minutes of fame per The Grauniad I related my Eureka moment when after months of searching, I found the birth registration of Emma Joan Brunel, coincidentally on the birthday of my own daughter Emma. But there have been other such occasions, and following far more abstruse research than for Emma Brunel. My first book was about Henry John Hatch, an unfortunate clergyman who endured six months’ chokey in Newgate. He and his wife adopted an orphan child, Lucy, and not knowing her surname, I wanted to trace her place of birth to see if it would be possible to identify her. For several reasons, only the 1861 census was appropriate, and I tried many times without success to locate the family. All the census returns have now been transcribed and indexed, but as some of the handwriting in the original returns is truly dreadful, the quality of the transcriptions varies enormously. Nevertheless, it is possible to do searches on several words. Eventually, by trying different combinations of names, I found that ‘Henry John Hatch’ and his wife ‘Essie’ had been transcribed as ‘Henry J Watch’ and his wife ‘Elsie’. Lucy was born in Goring in Sussex; there were only two candidates fitting the dates, and I knew she was one of five children. The census returns confirmed that she must have been Lucy Buckler, and I found out much later via an independent route that that was indeed her name. But perhaps the most satisfying detection, which amply illustrates the unreliability of some of the official records, was finding my wife’s great-great-grandfather’s birth details. His name was Henry Thomas Doe, and he served in the Royal Navy all over the world, including a voyage to Australia, New Zealand and the South Sea Islands in HMS Basilisk. His story was published here. His naval record, recovered from the National Archives, stated that he was born in Great Bookham, Surrey, on 12 August 1853, but there was no corresponding record in central registration. This is unusual but not greatly so, so I looked at the parish records. There was no record there either, but what there was, was this: Harriet Thomas Dow, baptised 13 November 1853 … Looking this name up in central registration yielded Harry Thomas Dow. The birth certificate when it came: The date of birth was one day out, but the father’s name, profession and mother’s name tallied, so Harriet Thomas Dow had morphed into Henry Thomas Doe via Harry Thomas Dow. It remains the first time that such an investigation has yielded a sex change...

Isambard Harrison, Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s great nephew, was working as an articled clerk for a solicitor in Brighton in 1911, but in September 1918 he turned up in Minnesota City, USA, employed by a farmer. The event was recorded on a Draft registration form he was required to fill in.

Why was he there? If it was a ‘gap’ year, he was somewhat late in doing it since he was 33 years old. And solicitor's clerk to farm-hand? I suggested previously, perhaps a little uncharitably, that he might have been dodging conscription; the USA had come into the war in 1917, but he could have arrived much earlier. By September 1918 it was clear that the allies were going to win the war, so there was little danger that Isambard would be drafted; in any event he was required to register. His full name appeared on the card – Isambard Joseph Francis Brunel Harrison – but he then proceeded apparently to provide a false next of kin: ‘John Brunel Harrison (Bro[ther]), 87 Kings Road, Windsor, London, England.’ But he didn’t have a brother. His father had noted on the 1911 census return – in which Isambard had been listed – that he had had only had four children, and that they were all alive – three girls and a boy. Also, his father’s name was just ‘John Harrison’ without the Brunel name. It is possible that the registrar misheard the relationship and it is also just possible that Isambard was under the mistaken impression that his father’s middle name was ‘Brunel’ – like Isambard's sisters. However, in 1911 the family were living in Brighton, and when Isambard’s mother died in 1922, it was in Droxford, near Portsmouth. Isambard did return at some point. His death at the age of 53 was registered in Builth Wells, Wales, in 1939. His youngest sister, Josephine Brunel Hensleigh Harrison, was granted administration of his estate which amounted to £206 19s 9d. Isambard Joseph Francis Brunel Harrison remains a mysterious figure about whom I would be fascinated to learn more. I find myself doing what I have never done before, turning the news off because it is so depressing. Of course a crisis is meat and drink to the news media, but I do wonder whether they are overdoing it; the ‘isn’t it awful?’ syndrome, ‘Let’s just have another look…’

It is a moot point whether we should maintain the scary news – deaths at a thousand a day and pictures of piles of coffins in temporary mass graves – in order to convince waverers or the bloody-minded that we must stick to the lockdown to save ourselves. But the downside of this is that we risk driving millions of people into clinical depression and paranoia. On the other hand we could lighten the news, point out that while many are dying, very, very many more are recovering – the prime minister and the heir to the throne to name but two. The danger with that strategy, is that people stop taking the situation seriously, which it undoubtedly is. On reflection, I think that I incline to a little more of the latter, and slightly less of the former for the sanity of all us all. Emma Joan Brunel was three years and three days older than her illustrious brother, but whether by accident or design it is on the anniversary of her birthday, 6 April, rather than his, 9 April, that the rising sun penetrates right through Isambard’s wonderful Box Tunnel on the Great Western Railway. The publicity attaching to this circumstance, following a recent article in the national press – based itself on an article I wrote for Genealogists’ Magazine in 2016 – led me to speculate on the possibility that Emma Joan might have direct descendants still living.

Emma Joan Brunel married George Harrison, a widowed curate, and in 1844 when George was the incumbent of the parish of New Brentford (coincidentally, where I went to school…), she gave birth to her only child, John Harrison. John enjoyed a privileged upbringing, initially having a nurse and then a private tutor. He attended Magdalen Hall College, Oxford, but there is no evidence that he took his degree. There is also no evidence that he ever worked for his living; every census record that I have found records that he was living on ‘private means…’ Nevertheless, he did get married; in June 1868 he wed the 17-year-old Lucy Maria Elizabeth Tucker. Their children were: Rosa Lucretia Brunel Harrison, born 1870 Mary Emma Lucy Brunel Harrison, born around 1884 Isambard Joseph Francis Brunel Harrison, born 7 Sep 1885 Josephine Brunel Hensleigh (or Hemsleigh) Harrison, born around 1889 The 14 year gap between the first and second children is odd, but Harrison's declaration in the 1911 census states that they had only four children and none that had died. Of those children, Mary and Josephine died spinsters. Isambard was in America in 1918, although he did return to the UK and died in Wales in 1939. He was a bit of a mystery; in 1911 he is listed as a solicitor’s articled clerk in Brighton, but in 1918, he was working for a farmer in Minnesota. Did he go to America to avoid being called up? There is no indication that he ever married; his sister Josephine was awarded probate on his death. Rosa is the real mystery. There is no obvious record of a marriage or death, and she seems not to have been included on the civil registration lists for births. Possibly she emigrated; after 1891 she just disappears. And that is as far as I have got. If there are any intrepid Harrison genealogists out there who can throw any light on the mysterious Rosa, I would be delighted to hear from them. Ditto anyone in the USA who has ever come across Isambard Harrison. If Rosa had children, then there is the possibility that Emma Joan Brunel’s descendants might be alive today. Post amended 24 April 2020, on receipt of Emma Joan Brunel's will, and the discovery that her eldest grand-daughter's name was Rosa Lucretia Brunel Harrison. Those nice people at The Guardian newspaper have published a review of my theory that Brunel aligned the Box Tunnel on the Great Western Railway such that the rising sun shone through it on the birthday of his sister Emma. You can read The Guardian article here, and my original piece here.

Added later: The story has now made it in an expanded version into the Daily Mail online here ... |

AuthorWelcome to the Mirli Books blog written by Peter Maggs Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed