|

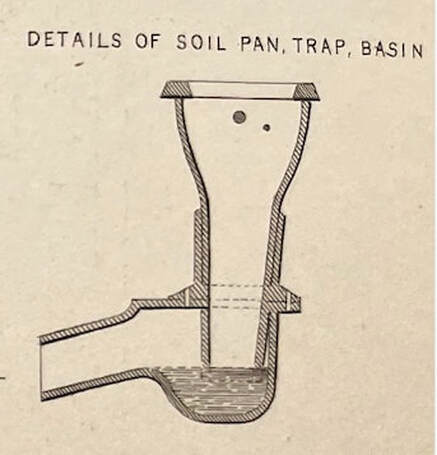

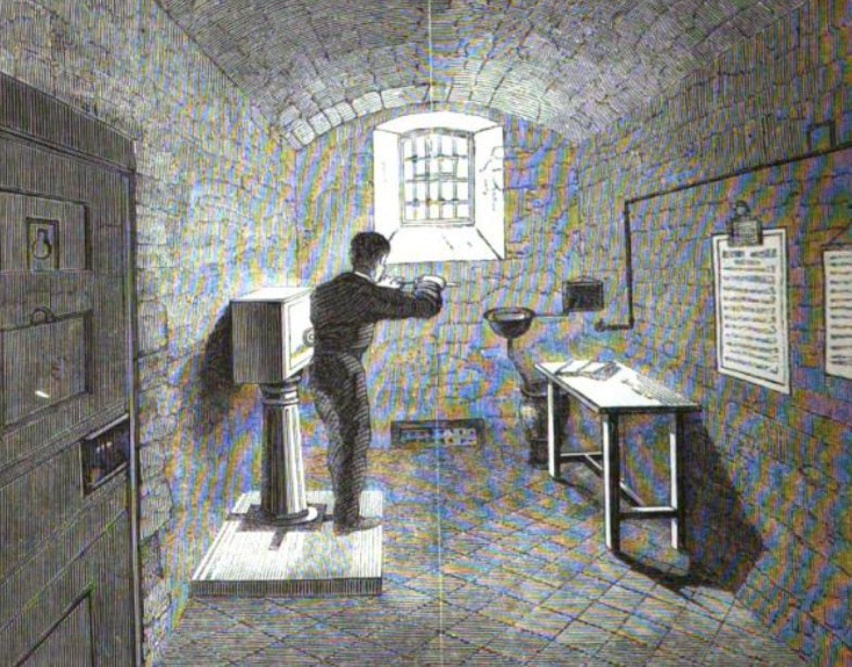

The establishment we know today as Wandsworth Prison was opened in 1851 as the New Surrey House of Correction. Men, women, and children—some as young as seven years old—served sentences there of between seven days and two years, with or without hard labour. The Surrey magistrates responsible for the institution decided that it should operate a new system of discipline known as the Separate System. The basic premise was that all communication between prisoners was forbidden, and this would act as a considerable deterrent. However inmates would have contact with the prison chaplain as well as various teachers and instructors of trades, and this was supposed to ensure that the punishment of imprisonment would be tempered by some real rehabilitation of the offenders. Prisoners were let out of their cells for around one hour per day for exercise; some of them had to perform hard labour turning cranks to pump water, or grind corn. Others were required to work in the laundry or kitchen, or clean the prison. While out of their cells, strict silence was observed and the prisoners wore masks over their faces to prevent other prisoners recognizing them. For religious worship on a Sunday, masks were considered inappropriate, so in order to effect separation the chapel was fitted with 400 vertical coffin-like structures with one prisoner inside each. Only their heads and shoulders were visible, and the sides and back of the ‘coffin’ prevented them from seeing or communicating with their neighbour... Most prisoners would spend twenty-three hours of each day in their cell. There they slept, washed, ate, and worked, and a few of them studied. Work could be picking oakum—shredding old rope for use in caulking—shoe making or mat making. Prisoners on hard labour were provided with a labour machine. This consisted of a crank turning a wheel, which was fitted with weight-operated brakes to make it hard to turn. Around 12,000 revolutions per day were usually required to ensure three meals per day... An obvious consequence of near twenty-four hour occupation of the cells, was that heating and lighting were needed during the winter months, and sanitary arrangements had to be provided all year round. Wandsworth prison had around 750 cells when it opened in 1851. With the exception of a few punishment cells, each one was air-conditioned and heated, lit by gas, and had en suite facilities and room-service. The prison was plumbed throughout for water—pumped by the prisoners from a deep well into tanks on the prison roof. There was also a small gasworks providing coal gas for lighting in the cells and elsewhere. In the corner of each cell was a lavatory pan complete with ‘soil trap’ with the output connected to a down-pipe which emptied into storage tanks. Water from a tap filled a washbasin, which drained into the lavatory; water for ‘flushing’ was provided by a separate pipe plumbed into the pan. The contemporary illustration shows the layout of a typical cell with the prisoner working the ‘Crank’ labour machine. The room service was a bell pull which operated a bell and little flag outside the cell to indicate which bell had been sounded. The warders were required to operate the water taps in order not to waste water, and very probably provide a light for the gas lighting.  There was much debate in the press and elsewhere regarding both the merits of the Separate System and the efficiency of its practical implementation. The use of masks outside the cells was abandoned after a few years as being both impractical and ineffective. A report to Hampshire magistrates in 1861 regarding the stalls in their chapel at Winchester, stated that each one was covered in obscene graffiti, and the prisoners ‘whispered’ to each other during services; sometimes they made a ‘great noise’. Shortly afterwards, the stalls were removed. Perhaps there was better control at Wandsworth; their individual chapel-stalls were not removed until 1880. However, urban myth number 492, which I have seen repeated on numerous web pages and in print, is that the lavatories were removed from the cells at Wandsworth ‘in the 1870s’ and replaced with ‘slopping out’ pails in order to free up space for multiple occupancy. It is quite clear from the picture that the lavatory occupied just a corner of the cell; no more room, in fact, than a slopping out pail. Furthermore, when beds were finally added to the cells—previously the prisoners had slept in hammocks strung between hooks in the walls—they were bunk beds. These took up no more room on the floor than a single bed, and present day pictures of cells at Wandsworth show that they were placed along the wall where the labour machine stood. Reference to the reports of the inspectors of prisons shows that the individual lavatories in cells were removed from Wandsworth between 1885 and 1886. But two years later, the record shows that separation was in most cases still adhered to, with the average number of prisoners very close to the number of cells. Exceptions were ‘the mentally affected’, and those suffering from depression or physical infirmity; they were deliberately accompanied by an able-bodied prisoner for companionship and assistance. Furthermore, overall prisoner numbers were falling, and since 1877 the prisons had been under national government, rather than county, control. Excessive numbers could be shipped around the country to wherever there was room. So if the lavatories were not removed to make room for more prisoners, why were they taken away? The answer is simple and prosaic: they didn’t work... (Those of a sensitive disposition might wish to skip the next few paragraphs...) Virtually everyone in the so-called ‘developed’ world uses a flushing lavatory with a cistern. In times of drought, we used to be exhorted to put a house brick in our lavatory cistern to reduce the amount of water used in each flush. Most lavatories these days have a double-flush facility, allowing the use of less water when ‘solids’ are not present. But anyone who has used a flushing lavatory knows that there are occasionally times when two or even three flushes are insufficient to remove the offending material. Then, and in the absence of Billy Connolly’s famous ‘Jobbie Weecha’ (Google it if you have no idea what this means; his speculation is hilarious), it is necessary to resort to desperate measures, frequently to the extreme embarrassment of the person concerned. The pioneers of modern flushing lavatories—take a bow Thomas Crapper—realized early on that proper, consistent, and hygienic operation required a large volume of water to be delivered in a short time. The main reason for this is that ‘solids’ have to negotiate the famous ‘U’ bend. The U bend is necessary since it provides a water seal against unpleasant smells emanating from the sewer. The early sanitary engineers recognized this issue, but for them far more important than ‘unpleasant smells’ was the ‘miasma’ theory of disease transmission. This was the belief that foul air could carry infectious diseases like cholera. The design adopted for the units in the prison is shown in the picture. A variation of this arrangement, known as a ‘bottle’ trap, tends to be used for sinks and wash-hand basins today; it takes up less space than a U bend and operates quite satisfactorily with liquids. A smooth U bend without joins, as used in all modern lavatory pans, offers a minimum of mechanical resistance to solids. It is clear from the picture that that is not the case with the ‘soil pans’ used in the prison. In fact the whole story becomes clear from the illustration—which is from a book published in 1844 by Colonel Joshua Jebb, the designer of Pentonville prison and consultant for Wandsworth. The units were manufactured in two parts—the joins and fixing points are clearly visible—probably because they were easier to fabricate that way (and also to enable them to be disassembled in order to deal with ‘blockages’). The first thing to notice is the inefficiency of the trap itself, and the strong likelihood of blockages. The bottom of the vertical part barely touches the water, and while this reduces to some extent the chicane effect of the trap, it means that the seal is barely made. Any variation in the manufacturing process, or a poorly assembled (or reassembled) unit could easily break the water seal rendering it ineffective. The two dots near the top of the unit are not faults in the printing process, but the inputs for two water pipes—one is the drain from the wash-hand basin, the other is water for flushing. From one of the other drawings in the book, it is clear that the larger hole is the connection for water for flushing, which comes directly from the pipes with no cistern to provide an adequately large and rapidly-flowing volume of water. A contemporary report from Pentonville, which used the identical system as Wandsworth, states that the ‘water closets’ were replaced by ‘communal, evil-smelling “recesses” because they were constantly getting blocked...’ On the question of the effectiveness of the Separate System of prison discipline itself, it was observed even before 1850—after Pentonville had been operating the Separate System for some years—that the process of isolating the prisoners from their fellows resulted in a rate of insanity ten times higher than in the population at large. Even at the height of the Separate System at Wandsworth, vulnerable prisoners were provided with cell-mates. One by one all of the specific aspects of ‘Separation’ were dropped, including the sole occupancy of prison cells. Although even now, as a recent Freedom of Information Request demonstrates, of 1,562 prisoners at Wandsworth Prison, only 835—just over half—are sharing cells, and in no case are there more than two persons to a cell. This analysis also demonstrates the importance to us of the invention of the efficient flushing lavatory, a considerable ‘convenience’ to all. It was realized in the late nineteenth century, and the experience at Pentonville, Wandsworth, and elsewhere probably contributed to the conclusion, that for proper operation, a really substantial flush was needed. Thomas Crapper’s main claim to fame was the invention of the syphon flush which delivered the volume of water required, while the cistern would then seal, allowing a slow refill without water leakage. When he died in 1910, he left nearly fifteen thousand pounds, worth close on to £2M today. As Thomas himself might have said: ‘It may be shit to you, but it’s my bread and butter...’

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWelcome to the Mirli Books blog written by Peter Maggs Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed